The Hidden Economics of Reading Habits: How readers and non-readers differ in everyday spending

By Eloquent Shelf

Published: November 18, 2025

8 mins

People make lots of assumptions about readers. Assumptions about intelligence, introversion and frugality. However, what if the real story isn’t about personality or preferences, but about priorities?

We’re using BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey data to explore how reading habits correlate with spending patterns across life categories. What is the economics of reading?

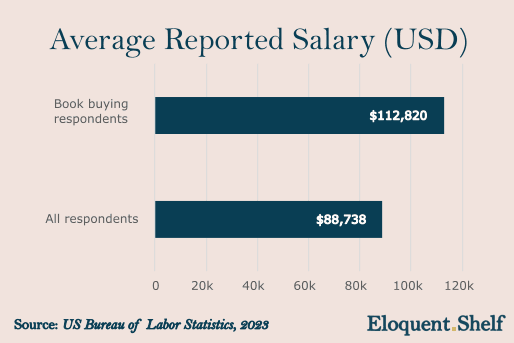

Salary data

The first data point we thought to explore was whether salary differed between readers and non-readers. We wondered whether the practice of reading correlated with higher income. The average reported salary for those respondents who reported buying books was $112,820 - that's over $24k more than the average reported income across the survey, more than a 27% difference. If there was ever a monetary incentive to read more, there it is. Perhaps, we thought, reading is a cost-effective means of self-actualisation.

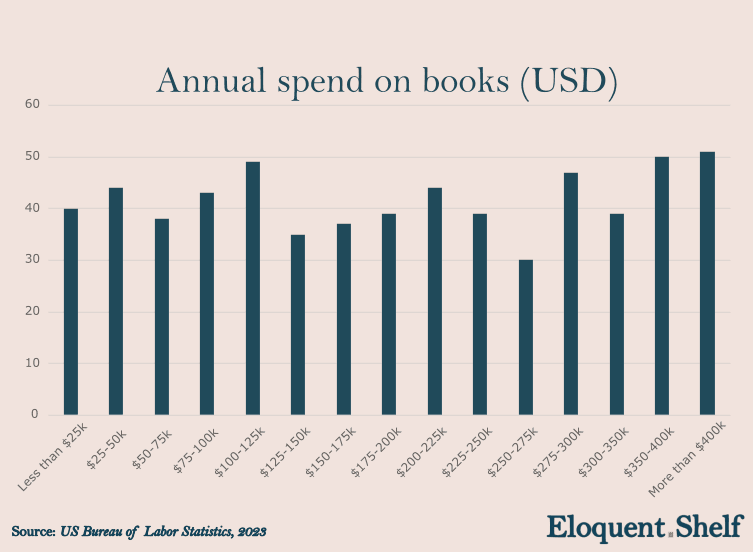

The average amount spent on books was $43 per year. This was the mean across all book-buying respondents, and it got us wondering about the distribution of book-buying among book-readers. We decided to group salaries into $25k pockets and measure what the average annual expenditure on books was for each salary range. Here are the results:

As you can see, there's no clear trend. We expected to see a clear dose-response relationship, given the strong connection between book-buying and overall salary... but it seems to be the case that book-lovers are book-lovers, whether they earn more or less than the average. It should be noted that the biggest spending categories were the two highest categories with salaries above $350k, however the gap between that and the third highest category ($100-125k) is only marginal. Perhaps for many readers, books are one of the cheapest lifelong-learning investments.

So book-buying does correlate with a higher salary, but the interaction is anything but a straight line. As a side note, we also explored how many people bought an e-reader device (such as the Kindle) and what their spending habits were. We found that only 3.34% of respondents bought a digital e-reader. That was 305 out of 9,013 respondents for that section of the survey. The average spend on an e-reader device purchase was $338. We also found that the average salary for those who purchased their e-reader online was $97,535, compared to $90,893 for those that shopped in-store.

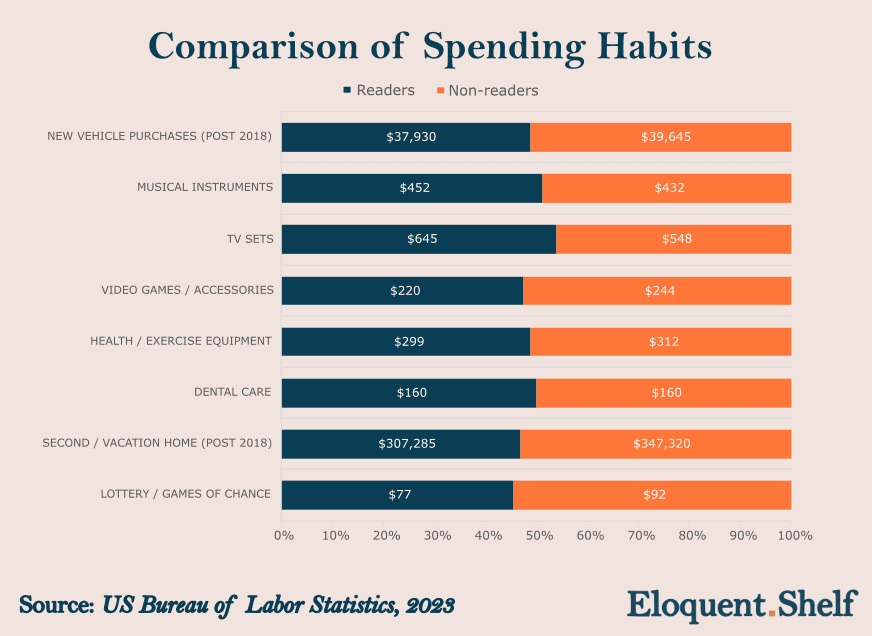

So then we dove into the stats, to determine how readers (those who reported buying books) differed in their everyday spending habits from those who choose not to read (those who didn't report any book expenditure). Here's what we found:

Entertainment and Gambling

One of the biggest differences were the expenses on impulse categories such as lottery tickets or video games. Readers spent approximately $20 less than non-readers in each of these areas per annum - perhaps an indication that they are more thoughtful and less impulsive about their spending habits. Or perhaps reading takes up time that they would otherwise spend in these areas. In any case, there appears to be a real and signficant difference between the two groups.

Health and Lifestyle

There was no drastic trend here. They shared the exact same dental health costs per year ($160), and non-readers actually spent more on health and exercise equipment. Perhaps this shows that non-readers trade the cognitive and intellectual benefits of reading for the physical and wellbeing benefits of exercise. However, the difference was small (only ~1%) and therefore is not likely to be statistically significant. One thing is for sure, reading doesn't produce monks or athletes.

Big Life Purchases

We looked at two key areas - purchase prices of newly bought vehicles and second homes. We only looked at vehicles that were purchased brand new, and second homes were defined as a non-primary residence, a vacation home, a recreational property, or a timeshare.

Our research uncovered an unexpected trend. That non-readers spend substantially more on big-ticket items, despite their being less likely to earn a higher income. Non-readers spent an average of $39,645 on brand new cars - that's $1,715 more than reader respondents. We also found that non-readers spent big when purchasing second homes. Non-readers shelled out an average of $347,320 on their second homes - compared to the average reader expenditure of $307,285. That's significantly higher from the non-readers - more than 13% more!

It's difficult to identify the exact reason for these differences. Perhaps it's about negotiating ability, or the importance placed on status symbols, or just a matter of how materialistic these groups are compared to one another. Perhaps there is a geographic component to consider. But one thing is clear, that the priorities of these two groups diverges significantly when we consider their expenditure on big items such as cars or houses.

So what do the statistics tell us about the spending habits of readers vs non-readers? It's hard not to draw the conclusion that readers exercise more financial restraint. They tend to earn significantly more, but spend less on the big purchases. Readers are more likely to prioritise expenditures on creative areas (such as TV sets or musical instruments) than non-readers, implying an affinity for the conceptual - perhaps rooted in their reading habits. Non-readers, in contrast, are more likely to prioritise expenditure on more impulsive purchases, such as video games and gambling.

Some key caveats should be noted however. Firstly, correlation does not equate causality; this is not evidence that reading results in more responsible spending or a higher income - it may be that both are causes of something else, such as IQ or upbringing. Secondly, the BLS survey data doesn't provide key information needed to fully contextualise the subject. We know that the books in question are not educational or academic books - but we don't know how many books the "readers" are actually reading - nor do we know whether "non-readers" are instead using libraries. We collate the data and inspect it with some accepted presumptions, with the hope that these presumptions are validated by sample size. While there appear to be some key and fitting trends which indicate variances across the two categories, those variances may or may not be as significant as this data indicates.

What we do know: reading isn't expensive. There are real, known benefits of reading. It's a habit that can replace less rewarding habits. If you're looking for a habit that offers some of the highest life-returns, look no further than a good book. The data of this research suggests that readers behave with slightly more intentionality across spending categories, and in general, earn significantly more the average wage. If reading shapes how we think, then perhaps it also shapes how we live.

Methodology:

All data was taken from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey (Interview Dataset) for the year 2023. Averages for expediture on products were calculated using the mean of total expenditures on products, not including those reported as gifts and discounting any repsondents who did not purchase the specific item or product. In the case of identifying "readers", we collated a list of all the identifiers for respondents who reported buying (non-academic, not bought through a book club subscription) books, and categorised all respondents into a category of "reader" or "non-reader" based on their existence in that list. The average salary was calculated as the mean of the reported income of all respondents across the entire survey.

Discover Your New Favourite Book!

Answer 5 questions and let our AI discovery tool recommend your next read. It's free, takes less than a minute and could change your life.

Perfect for you or a gift for someone thoughtful.

Sign up for our Newsletter

Join our weekly newsletter to stay updated on the latest non-fiction recommendations and insights.